THE CONSERVATIVE

COMPUTER

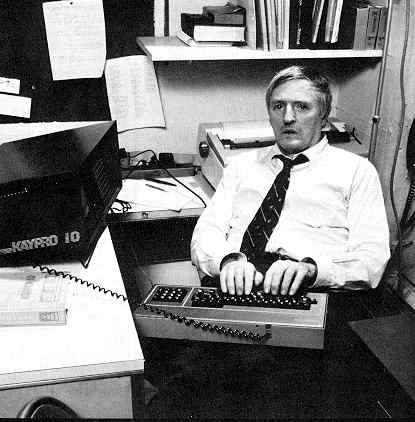

by Wm, F. Buckley, Jr.

Wm. F. Buckley, Jr., is the editor of National Review. He is the author of numerous books, including the Blackford Oaks series of spy novels.

I have heard more guff from my brothers in the conservative and libertarian movements on the subject of computers than on any other that comes to mind-and none does, since we are generally all correct about everything. The assault is at every level. My brother George Will seems to be saying that you cannot love the written word unless you set it down by pencil on a legal pad. The California libertarians declared war several years ago against a projected identifying number that would permit taxonomizing an American via computer in a matter of seconds. Well, well.

It is the primary contention of the conservative faith that we are individuals. That in order to stress that individuality we need as few collective social assertions as possible. This is an invitation not to solipsism, but rather to continued, relentless individuation. We get this primarily, I think, from the Bible, in which, at a most important level, there exists only God and the individual's soul, the saving of which is his superordinate responsibility. Perhaps he can do this by the ultimate immersion in communal life. Still he stands out as an individual, even as Mother Teresa stands out as an individual.

Along come the computers, and they throw a new light on the question. Not only is the computer capable of distinguishing John Jay Jones of Shaker Heights, Illinois, from John Jay Jones of Winesburg, Ohio; it can also tell us that Mr. Jones from Ohio has had his appendix removed, whereas the other Jones has not. And this could be a life-saving datum-don't ask me to give you the scenario, do it.

The notion that to carry an identifying number is to surrender privacy is so wrong as to be exactly the opposite of the truth. If we have individual fingerprints, why not an individual number? And while on the subject, what objection can we reasonably have to giving out our fingerprints to a computer? The conservative dream of maintaining one's individuality in a highly technical age is surely advanced, rather than retarded, by this capacity to mark everyone's uniqueness. The collectivizing mania, where gradually the individual disappears to be replaced by classes, groups, professions, is surely set back by this means, no?

I have recently subscribed to an electronic communications system (Telenet) that gives you a password. But mark this: the password is so secret that when you tap it on your screen you yourself cannot discern its letters. This means that you carry in your memory or in your notebook eight letters with the aid of which, computer in lap, you can communicate instantly with anyone who also subscribes to that service. And if you do not wish to give out that number, this side of torture I know of no way it can be got from you. Such strengthening of individual powers appeals greatly, or should, to conservatives.

For us, also, there is the eternal quarrel about the market. Conservatives believe simultaneously that a) the free market will yield the correct social-economic decision, and b) the "correctness" of that decision is purely utilitarian. The People can vote Dallas the best program on television, and we can distinguish between whether Dallas is worth looking at and whether it is right that people have it. Yes to the latter, no to the former.

The computer is going quickly to reduce the distance between the individual and the supplier. Companies can often go broke before they can transcribe the public reaction to their products. The antennae focused on the public will in the past have been rudimentary. You have for many years been able to get instant reactions to, e.g., a new rock release. The disk jockeys will know within a matter of hours whether they have a winner. But this is not so concerning, for instance, a new model of automobile.

Computer speed cannot help to advertise a poet's freshly minted sonnet, or a classical composer's new oratorio, because these have built-in counterinertial forces that prevent, in all but a few cases (Eliot's Prufrock, Verdi's Rigoletto) instant acclaim. But if we put high emphasis on consumer satisfaction, and consumer sovereignty over market forces, why should we look with dismay at the discovery of the means by which the consumer's will can decisively assert itself?

The list of computer benefits is so very long. I mentioned my old friend John Jay Jones who needs his appendix taken out. The computer, we are told, will accelerate and render more accurate diagnostic work in the days to come and why should we object if a country doctor, with the aid of a data bank, can discover that the baby has a rare disease, rather than discovering what that disease was in an autopsy?

And, of course, there is word processing. John C. Calhoun, one of his biographers once wrote, had such powers of concentration that when tilling the soil on his farm his mind was working to compose his speeches. When he came in from the farm, he was left with a purely mechanical chore: that of transcribing his own memory. But tedious stuff this, since I do not understand why anyone should take pleasure in the act of handwriting (any more than I see why anyone should take pleasure in the act of tilling). Writing is menial work. It is not artistic, unless one is a calligrapher. So then, why not attempt to abbreviate that work? The arguments against using a word processor instead of a typewriter are not different in kind from those against using a typewriter in place of a pencil. I find them as reasonable as arguments against using an airplane instead of an automobile, or an automobile instead of a horse, if the idea is to arrive, as distinguished from, say, to enjoy a horseback ride.

Enough people by now know what a word processor does to make unnecessary the recounting of its versatility. It is resistance to it that absolutely confounds. And the notion that this resistance is widely deemed to be conservative is to reinforce the stereotype of the conservative as someone who cannot appreciate that which is self-evidently progressive. I fear that I know people among my closest ideological friends whose forebears must have looked suspiciously upon the wheel.

Well, then, there is only one thing for it. Progressive conservatives should pass a law making it unlawful not to use a computer.

Return to Table of Contents | Previous Article | Next Article