AND MACHINES

The computer in science fiction

by Michael Kurland

Michael Kurland is a novelist with

over twenty published books, one of which, The Infernal Device, was nominated for an American Book Award.

The joke goes like

this: A group of computer geniuses get together to build the world's

largest, most powerful thinking machine. They program it with the

latest heuristic software so it can learn, then feed into it the total

sum of mankind's knowledge from every source-historical, scientific,

technical, literary, mythical, religious, occult. Then, at the great

unveiling, the group leader feeds the computer its first question:

"Is there a god?"

"There is now," the computer replies.

As a joke, this story takes four sentences. As a

movie (Colossus: The Forbin Project or

WarGames), it takes up to two

hours. As a novel (The Humanoids

by Jack Williamson or Destination:

Void by Frank Herbert), it takes a whole book.

This perverse deus

ex machina view of computers was

explored by science-fiction writers in the fifties, probably first in a

story called "Answer" in Angels and

Spaceships by Frederic Brown. But

"thinking machines" were described in science fiction and fantasy

literature long before UNIVAC started blowing fuses and tubes-even

before Charles Babbage began turning cranks. Over the centuries there

has been a fascination with the notion of artificial beings or

artificial intelligence, and the legendary mark of a true master of

occult or metaphysical science was his ability to construct such a

contraption.

Golems to Go

In the sixteenth century the great Rabbi Judah Loew of Prague created a

golem, a being of clay, and animated it by certain mystical rites,

culminating with placing in its mouth a parchment on which was written

the secret name of God. According to the legend, the creature knew

neither good nor bad, but all its actions were like those of an

automatic machine obeying the commands of the person who animated it.

It was also believed that of the three sorts of

cabalistic intelligence, Daat, Chochmah and Bina (knowledge, wisdom and

judgment), the golem was possessed only of Daat. Wisdom and judgment

were beyond it. This is illustrated by what happened when Rabbi Loew's

wife asked the golem to fill two large water kegs in her kitchen: the

golem took two pails and went to the brook; however, she'd forgotten to

tell the golem to stop when the kegs were full-with, as any programmer

can tell you, predictable results.

Years later, in the Oz books written. at the

beginning of this century, L. Frank Baum introduced a character called

Tik Tok, the mechanical man. Tik Tok, though slight-ly me-chan-i-cal in

talk-ing, moved and thought pretty much like a flesh-and-blood person.

He just had to be wound up every once in a while.

Some authors, in envisioning a mechanical brain,

merely took those things that they knew and advanced them one step

further. In Thrilling Wonder Stories

magazine for fall 1944, Paul

MacNamara had a novelette called "The Last Man in New York" in which he

described a strange device:

At first glance the colossal machine looked like an over-sized newspaper press. A second glance showed that it was a super-adding machine-an adding machine to end all adding machines. Atop this unbelievable pile of equipment which was more than five stories tall, a row of digits which ran into some sixty figures was constantly changing, increasing the growing total.

Imperfect Prophet

Though a literature based mainly in the future is bound to make a few

lucky guesses, science fiction often missed the mark when it came to

how computers would work. On the other hand, imagine having to predict

what computers will look like and be used for in, say, fifty years. The

only thing we can be sure of is that in fifty years computers will be

used for things we cannot now imagine.

In the 1942 novel Beyond

This Horizon, Robert

Heinlein described the computer as a "huge integrating accumulator." As

Heinlein explained it: "All of these symbols ... passed through the

bottleneck formed by Monroe-Alpha's computer, and appeared there in

terms of angular speeds, settings of three-dimensional cams, relative

positions of interacting levers, et complex cetera. The manifold

constituted a dynamic abstracted structural picture of the economic

flow of a hemisphere."

This was a good guess for 1942, but the truth proved

both simpler and more elegant. Whereas Heinlein's "integrating

accumulator" solved simultaneous high-level equations and accumulated

the results, a modern computer can't do that; all it can do is add,

subtract and perform logical operations in binary. But it does this so

fast that all else is possible.

Heinlein was right on target, however, with his view

of how all-important the computer might become once it existed. The

gadget in his book was running the economy. "What would happen," one

character asks another, if I took an ax and just smashed your little

toy?"

". . . it would result in a series of panics and

booms of the most nineteenth-century type," his friend replies.

"Carried to extreme, it could even result in warfare."

Twenty-four years later, in his book The Moon Is a

Harsh Mistress, Heinlein showed that he had learned the secret

of

describing computers: use lots of technical jargon and acronyms. His

machine, a super-bright computer that just about controlled the moon,

was a "High-Optional, Logical, Multi-Evaluating Supervisor, Mark IV,

Mod. L-a HOLMES FOUR." Naturally, it was named Mycroft (Mike).

What did Mike do? "In May 2075, besides controlling

robot traffic and catapult and giving ballistic advice and/or control

for manned ships, Mike controlled the phone system for all Luna, same

for LunaTerra voice & video, handled air, water, temperature,

humidity, and sewage for Luna City, Novy Leningrad, and several smaller

warrens ... did accounting and payrolls for Luna Authority, and by

lease, same for many firms and banks."

Less than twenty years ago, a blink of the Cosmic

Eye, this brilliant writer predicting a hundred years into the future

was unable to see a change that was only ten years down the road.

Heinlein has one computer controlling an entire planet (all right,

moon). Today it seems more probable that there will be two or three

computers in every house.

A Parent Figure

One giant computer that knows all, sees all, does all, even a

beneficent one that means nothing but good, could be a very destructive

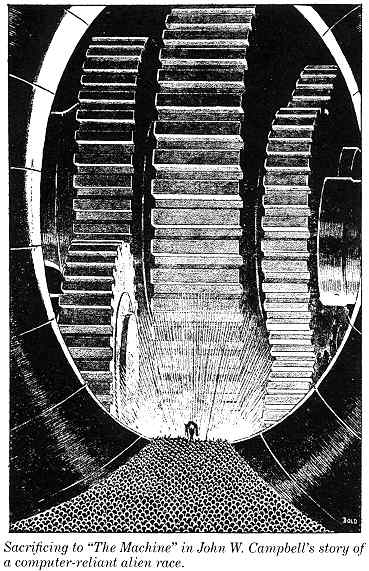

thing for the human race-as was foreseen by John W Campbell in a 1935

story from Astounding Science-Fiction,

"The Machine."

[The Machine's] progress meant gradual branching out, and as it increased in scope, it included in itself the other machines and took over their duties, and it expanded, and because it had been set to make a machine most helpful to the race of that planet, it went on and helped the race automatically.

It was a process so built into the Machine that it could not stop itself now, it could only improve its helpfulness to the race. More and more it did, till ... the Machine became all. It did all. It must, for that was being more helpful to the race, as it had been set to do, and had made itself to be.

The process went on for twenty-one thousand and ninety-three years, and for all but two hundred and thirty-two of those years, the Machine had done anything within its capabilities demanded by the race, and it was not till the last seventy-eight years that the Machine developed itself to the point of recognizing the beneficence of punishment and of refusal.

Behaving like the ultimate parental figure, the Machine began to refuse requests when they were ultimately damaging to the race. And because they no longer understood its workings, the members came to call the Machine "what you would express by God" and sacrificed young females in the hope that it would start up again. Finally, in order to stop this slide back down to savagery, the Machine was forced to leave the planet-and leave the race to fend for itself in rebuilding its civilization. The thesis here is that if you do too much for people, they forget how to do for themselves. Or perhaps: God helps those who help themselves.

"The Cosmic Blinker" sends a message to this computer in Eando Binder's 1953 story, right; art by Frank R. Paul.

Astounding Androids

In 1949 Jack Williamson, in The Humanoids, created a race of robots whose built-in injunction was "to serve and obey, and to guard men from harm." They did this so well that a fellow could not cut up a lamb chop or shave his face without having a friendly robot come and take the dangerous sharp instrument away from him. You have to be careful how you phrase things around completely logical machines. (Larry Niven, in a 1976 story from Galaxy magazine called "Down and Out," gave some very good advice along that line: "Never say forget it to a computer."

Robots have not always been pictured as being all-important. They had their mundane uses, too. In "A Bad Day for Sales," a 1953 story from Galaxy, Fritz Leiber introduced us to Robie, the world's first salesrobot, who rolled around the city all day vending lollipops and soft drinks.

In a series of stories in Astounding Science-Fiction in the early 1940s, Isaac Asimov postulated the invention of robots with "positronic brains." And to control their behavior he invented the famous Three Laws of Robotics. (Dr. Asimov credits John W Campbell, then editor of Astounding, with helping him lay down the law.) The Three Laws are sort of the Ten Commandments of our metal-clad brethren. As usually formulated, they are:

1) A robot shall not harm a human being nor, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

2) A robot shall obey the commands of a human being except when doing so would conflict with the first law.

3) A robot shall preserve its own existence, except when doing so would conflict with the first or second law.

With the rapid development of artificial intelligence, designers and programmers of advanced systems are taking a serious look at Dr. Asimov's three laws. If there's any way to implant them permanently in internal memory, I'm sure it will be done before computers get too much brighter and have many more movable appendages.

The problems will arise not when computers develop true intelligence, but when they become aware. In 2001: A Space Odyssey, Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick provided us with an alarming example of what can happen when an aware computer gets just the slightest bit bewildered. HAL 9000 (when computers become aware, they must have names) was the ship's computer on Discovery, a space vehicle on its way to Jupiter. If you saw the movie or read the book, you'll remember HAL's treachery: how it claimed the external antenna was misaligned and then blew one of the astronauts away when he went to investigate; how it disconnected the life-support system on three sleeping astronauts, leaving only one, Bowman, alive. Bowman proved that human intelligence and ingenuity are a match for even a supercomputer and gave Hal a lobotomy. It is a salutory lesson for us all. Dr. Asimov's three laws of robotics are to be ignored at our peril.

From Here to Eternity

Some religions hold that God set various tasks for man. In "The Nine Billion Names of God" (Star Science Fiction magazine, 1953) Arthur C. Clarke related the tale of a monastery that used a computer to complete its task: enumerating all the names of God. As it finished, the stars began winking out one by one.

What is the future of the computer in science fiction? It's clear that science fiction will have to fight hard to stay ahead or even abreast of fact in coping with the explosive rate of progress in this field. Fictional computers have already traveled to the ends of space and the beginning and end of time. Computers embedded in the user's brain and users embedded in the computer's brain have both been written about.

The area that remains to be thoroughly explored is how humans and the computer will interact-and how humans will interact with humans in the age of computers. Computers have fought humans and humans have fought computers. And in several stories computers have fought each other after the last humans have died.

Perhaps, if we're really lucky, we'll build a computer smart enough, crammed with enough Daat, Chochmah and Binat, to save us from ourselves while there's still time.

Return to Table of Contents | Previous Article | Next Article