MICROS

Computers and music

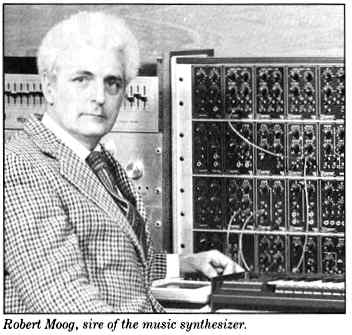

by Robert A. Moog

Robert A. Moog is the inventor of the

practical music synthesizer and president of Big Briar, Inc., a

Leicester, North Carolina, firm specializing in the design of custom

electronic instruments.

For some of us, the

idea of an electronic muse is scary; after all, music is an essentially

human activity, while electronic equipment, especially the computer, is

"mechanical" and "unnatural." Throughout history, however, music has

been closely linked to technology. Except for the human voice, the

instruments of music-making have always been "high tech" in their time.

The Electronic Muse

The violin, pipe organ and trumpet are complex constructions that were

as "unnatural" when they were first developed as the computer is today.

The piano and saxophone, those vital elements of our musical

experience, were triumphs of manufacturing technology a century ago.

Musical instrument designers have always employed the most advanced

technology of their time. Now, in our time, electronic and computer

technologies are preferred for new musical instrument development.

But this is not to say that musicians are embracing

electronics just because it's the "latest thing." As a group, musicians

favor instruments that a) sound good and b) offer musically useful ways

of manipulating sound. Increasingly, musicians are drawn to electronic

instruments-not because they're easy to play or sound like traditional

acoustic instruments, but because they offer new tone colors and new

ways of making music.

What's more, musicians have been experimenting with

electronic instruments ever since the vacuum tube was invented

three-quarters of a century ago. Even before that, musicians and

musical instrument builders were collaborating to harness the

forerunners of electronics and computers to the service of the muse.

For a growing number of musicians, computer

technology is the greatest advance since the invention of catgut. Music

is a form of communication-of organizing and transmitting data. The

"alphabet" of music consists of notes. Melodies, chords and rhythmic

patterns are the "words" and "phrases" of music. Just as computers can

generate "characters" to make text or a graphic design, they can also

process a stream of numbers that represent a sound waveform. And just

as word processing programs endear computers to wordsmiths, today's

composers, performers and music teachers are all exploring the

computer's ability to handle musical information.

If you understand the general principles of computer

operation and if you like to listen to music, you'll have no trouble

following the many ways that digital technology and computers can be

used to make music. Just keep in mind that computer music is a natural

extension of traditional music and uses programs that are only slightly

different from your basic word processor or data handler. As we shall

see, simulating a multitrack recording studio on your monitor screen is

done with software that is directly related to the program used to

"compose" this article.

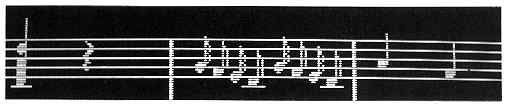

Musical Digits

All sounds, musical or otherwise, are vibrations of the air, at rates

of roughly 20 to 20,000 times a second. If the vibrations repeat

regularly, the sounds are pitched (like a guitar or clarinet tone). If

a sound vibration does not repeat regularly, then it sounds pitchless

or "noisy" (like a cymbal crash). In a pitched sound, the rate of

repetition is called its frequency; the greater the frequency, the

higher the musical pitch of the tone. The strength of a vibration is

called its amplitude; the greater a sound's amplitude, the louder it is.

The shape of a vibration is called the waveform. You

can think of the waveform of a sound as a graph of the air pressure at

a particular point over time. The waveform is an abstraction that we

use to describe the sound. It happens to be an abstraction that has a

lot to do with the tone's perceived quality.

A loudspeaker (speaker, for short) is a device that

converts electronic vibrations into sound. In talking about electronic

music and computers, we generally refer to electrical waveforms that

exist inside an instrument's circuitry. When we refer to these

waveforms as if they were sounds, we assume there's a speaker somewhere

and that we're using it to produce the sounds.

A personal computer may contain its own small

speaker (e.g., the Apple II), may use the speaker of the TV to which it

is connected (e.g., the Atari or Commodore 64) or may require

connection to an external sound system like most high-quality music

synthesizers. Most electronic pianos, organs and synthesizers use

"analog" circuits that produce smooth waveforms. Digital computer

circuits, on the other hand, work by switching on and off.

How does a computer produce a musical tone? In most

computers, you can turn the speaker on and off as if it were, say, a

memory location. You can produce a tone by writing a simple program to

a) turn the speaker current on, b) wait a very short time, c) turn the

speaker off, d) wait again, and e) repeat the above steps a specified

number of times. The waiting time determines the pitch of the tone,

while the number of cycles of repetition determines its duration.

If the "speaker on" and "speaker off" times are the

same, the resultant waveform is called a square wave and the musical

quality is somewhat hollow, like that of a clarinet. If the "speaker

on" and "speaker off" times are not the same, the waveform is called

"rectangular" and the quality may be saxophone- or oboe-like. If the

"speaker on" and "speaker off' times are programmed to change randomly,

the resultant sound is a pitchless noise.

While any computer can produce square and

rectangular waves, only those equipped with sound synthesizer circuits

can produce more complex waveforms. Some sound synthesizers are built

on single integrated circuit chips that can be progammed to produce a

wide variety of waveforms and envelopes. (The envelope of a sound is

its outline as it builds up, sustains and dies out.)

Other synthesizers are built on circuit cards that

plug into the computer or may be completely separate peripherals.

Computer programs enable musicians to design their own sounds.

Musicians think of this type of programming as "building an

instrument": the "instruments" exist as data that define waveforms and

envelopes-and may therefore be stored in "libraries" on disk or tape.

Computer-controlled sound synthesizers may be

all-digital (the waveform itself is generated from digital data),

all-analog (waveforms are produced continuously by analog circuitry

that responds to digital instructions) or a combination of the two

(waveforms are converted from digital to analog form, then passed

through analog circuitry). Digital circuits that produce waveforms

handle numbers that represent a succession of points along a waveform.

Analog circuits, on the other hand, handle voltages that change

continuously to generate the desired waveform.

Digital circuits are more accurate and reliable than

their analog counterparts. Since they produce waveforms from a series

of numbers in time, however, the resultant waveforms are made up of

steps that are often audible. Both methods of synthesis have their

advantages and limitations; some musicians prefer the smooth,

distortion-free analog waveforms, while others favor the accuracy and

versatility of digital generators.

Playing the PC

There are simple programs for most personal computers to make scales

and melodies through the computer's speaker. To use a typical progam of

this kind, you type in codes for the pitches and durations of the notes.

More sophisticated programs enable you to vary the

rectangular wave tone color, adjust the overall tempo, produce trills

and glides, and store tunes that you have programmed on disk or

cassette tape. Music Maker, a software package for the Apple II,

produces the illusion of two notes being played simultaneously,

generates sound effects as well as musical tones, and displays a

colorful animated video pattern in time with the music. Programs like

Music Maker don't produce complex or high-quality musical tones; their

main uses are educational and recreational-you can learn a good deal

about programming, train your ear and have a lot of fun, for a very

small investment in addition to your computer.

By using a computer with a built-in sound

synthesizer, or adding a digitally controlled synthesizer peripheral,

you can make music with a wide variety of interesting tone colors. The

Commodore 64 has one of the most versatile built-in synthesizers of any

currently available personal computer. The "64" uses a proprietary chip

that produces three tones with programmable waveform and envelope. The

chip also contains an analog filter, a device that changes the tone

color by emphasizing some of the sound's overtones and cutting out

others. The resulting range and quality of sound rival that of some of

the analog keyboard synthesizers available in musical instrument stores.

Some of the most musically advanced computer

programs are designed around the Mountain Computer Musicsystem, an

eight-voice digital tone generator for the Apple II. Among the more

popular are the Alpha Syntauri and the Soundchaser systems. Both use

the Musicsystem in combination with a professional-style four- or

five-octave music keyboard and their own operating software.

With either of these systems you can make up your

own sounds, play them from the music keyboard and record the keyboard

performance. Since one part of the software sets the Musicsystem up to

produce the desired tone colors and another part captures and stores

the keyboard performance, you can play back your keyboard performance

with a variety of tone colors, pitch ranges and speeds. Both the Alpha

Syntauri and the Soundchaser can implement the basic functions of a

multitrack recording studio. You can record a keyboard performance on

one "track," then play that track back while recording subsequent

tracks. The Syntauri Metatrak program, for instance, lets you record up

to sixteen tracks, then play them back simultaneously. Fast Forward,

Rewind, Record and Erase functions are implemented by typing one or two

characters on the computer keyboard.

To a musician, using Metatrack (or the Soundchaser

Turbotracks program) is closely akin to using a conventional tape

recorder. To the average computer user, programs that implement a

multitrack recorder are actually file management systems with real-time

merging capability. Whichever way you look at it, Metatrak, Turbotracks

and related programs offer potent musical resources to pro

musicians-and a lot of musical enjoyment to amateurs.

In addition to simulating multitrack recorders,

computer-based music systems offer other functions that are important

to musicians. Music-teaching programs are available for both the

Soundchaser and the Alpha Syntauri. Soundchaser's Musictutor package

contains an array of ear-training exercises that not only sharpen your

ears, but keep track of your learning progress. Syntauri's Simply Music

program will teach you how to play a keyboard instrument in a variety

of styles and at a pace that suits you. Once your keyboard chops are in

good shape, you can convert your keyboard performances directly to a

printed score with Syntauri's Composer's Assistant, a software package

that enables a dot-matrix printer to produce conventional music

notation.

Computer Control

The Roland Compumusic CMU-800R is an example of an analog musical sound

generator designed for computer control. The Compumusic uses electronic

piano, organ and synthesizer circuits to produce realistic percussion,

bass, "rhythm" guitar and melody voices through your sound system.

Using Roland-supplied software, you program the melody, harmony and

rhythm from the computer keyboard. Then you "mix" the sounds by

manipulating the volume sliders on the Compumusic unit while the

computer "plays" the complete piece of music that you've programmed.

The computer is not able to program the Compumusic waveforms since

these are determined by the unit's analog circuitry. The advantages of

Compumusic are in its high sound quality and hands-on-the-knobs control.

Musicians have expressed the desire to control a

regular electronic keyboard by means of a computer. An increasing

number of electronic pianos, organs and synthesizers are being adapted

for computer control. For this purpose, the musical instrument industry

has developed an interface called MIDI, the Musical Instrument Digital

Interface. MIDI allows electronic instruments, computers and similar

devices to be connected with a minimum of fuss. This means that, if

your computer itself is equipped with a MIDI peripheral and the

necessary software, you can use your computer to control any

MIDI-equipped electronic musical instrument. You can even combine

instruments into a computer-controlled "orchestra."

Will computers ever completely replace human

musicians? A number of traditional instrumentalists, upon seeing entire

string and horn sections replaced by synthesizers and other digital

instruments, have asked this question. The answer lies in the fact that

music is and always will be an aesthetic and emotional experience for

humans and not for computers. There will always be musicians as long as

there is a song in our hearts.

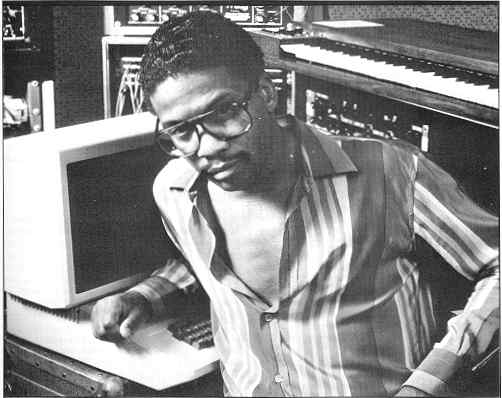

Herbie Hancock on the road with computer and clavier. THE MUSICIAN/MACHINE CONNECTION When I use a computer to make music, it's as if I have a partner-one that acts in a very logical way and appears to function like a human brain. The interaction causes a strange relationship. The computer gives me answers quickly and makes no mistakes. If I give it data that doesn't fit into what it can do, I say: "It doesn't like that." Or when it pauses, I tell myself: "It's thinking." There is definitely an intellectual challenge to make the computer do what I want. I have to communicate with it in a very specific way. I use a Fairlight computer to create sounds I can't get any other way. I can digitize sounds from actual instruments and then modify their waveforms on the screen with a light pen. This doesn't mean I intend to turn my back on traditional acoustic instruments. I'll continue to play acoustic as well as electronic keyboards, because every instrument has its own touch, texture and nuance. It's just that synthesizers and computers are tools for making instruments the likes of which have never been heard before. Some keyboard players are great performers on a synthesizer, but they don't know much about programming it. Others are good players and programmers. Thinking in musical terms can help develop your technique for programming computers. A musician thinks in terms of measures and themes; in programming you have to consider lines of code and routines. Of course, having manual dexterity also helps, since a prerequisite for using today's computers is the ability to key in commands. Someday, though, you'll be able simply to talk to computers with voice recognition. In the future I'd like to be able to create music on-line with anyone anywhere in the world. Recently I saw a concert in Vancouver where the musician on stage was playing with two other people in Sydney and Tokyo. The only limitation was the speed of the electrons on-line-the speed of light. There was a slight delay in the audio, and the musicians had to take risks with their playing to stay in sync. But here they were, playing together on three continents! It made me look forward to the day when the electronic cottage will become an electronic bandstand. HERBIE HANCOCK, creator of electronic keyboard albums including Headhunters and Future Shock |

| DIGITAL KEYBOARD INSTRUMENTS  Digital

computers are like farmers' tractors. A tractor is a source of

mechanical power, with a few levers to control that power; it's nearly

always used with specialized implements that may be simple (like a

plowshare) or larger and more complex than the tractor itself. Digital

computers are like farmers' tractors. A tractor is a source of

mechanical power, with a few levers to control that power; it's nearly

always used with specialized implements that may be simple (like a

plowshare) or larger and more complex than the tractor itself.A computer is a source of number processing power. Its own levers (the keyboard) give access to the power within. But it is the peripherals, like printers or digitally controlled synthesizers, that convert the computing power to some form of information or useful action. To understand the difference between a personal computer with a digitally controlled synthesizer peripheral and a digital keyboard instrument available in music stores, let's carry our tractor analogy a little further. Many implements contain their own sources of power and perform their functions without being hooked to a tractor (examples range from lawnmowers to fifty-ton bulldozers). In these implements, built-in power is more efficient and convenient than separating the source of power from the specialized mechanical function that gets the job done. Digital keyboard instruments are the musical counterparts to implements with dedicated power sources. At the heart of any digital keyboard is a specialized computer that is preprogrammed to perform a limited set of functions. The computer controls a digital synthesizer that actually produces the instrument's sounds. Although technically they are separate entities, computer and digital synthesizer are often built together and both are located inside the instrument. The player accesses the computer and plays the instrument by manipulating the panel controls and depressing keys. Digital keyboard instruments come in all sizes. The smallest ones are portable, inexpensive and funoriented-our folk instruments of the eighties. Most have built-in drum rhythms, and can remember and play back what you play on the keyboard. Some of the larger ones are complete home music centers that read the music, then play one part while you play the other, or teach you how to read music and play the keyboard. Others, designed for professional musicians, have a wide variety of rich tone colors, touch-sensitive keyboards and performance-oriented functions. The best of them produce accurate simulations of strings, acoustic piano and guitar, and electronic musical sounds of extremely high sonic quality. Up in the performance-price stratosphere are the "computer musical instruments"-large studio instruments controlled by full-blown dedicated computers. These instruments offer the state of the art in digital sound production and control. The Fairlight, for instance, records or synthesizes virtually any musical sound, then allows the musician to "play" the sound back at any pitch, either from its touch-sensitive music keyboard or from one of two special composing languages. The Synclavier, another superinstrument, is designed to develop sonically rich timbres by adding together "partial waveforms." With any of these superinstruments, a musician working in a studio can start at synthesis of the sounds and end with a complete multipart piece of music. This is why the superinstruments have found extensive use in film, TV and commercial music production houses. But are the superinstruments the ultimate computer musical instrument? Not by a long shot. Scientists and musicians at Lucasfilm have developed a multimillion-dollar system called the Lucasfilm Audio Signal Processor. The ASP is a completely digital recording studio, musical sound producer and film synchronizing facility all in one. In place of the time-consuming film sound editing and mixing traditionally done "by hand" to get music, dialog and sound effects into a movie or TV program, the ASP enables musicians and film sound people to computerize all aspects of sound track production. Digital technology is entering every area of music and sound production. As digital audio disks and tapes become commonplace, we can look forward to hearing the highest quality of reproduced sound in our homes-sound that is limited in quality only by the loudspeaker itself. The promise for digital musical instruments is equally bright: warm, rich timbres, vast creative potential, exciting interactive computer-aided teaching and performing modes. At the rate digital technology is advancing, musical instrument designers will soon have to deal with the same situation that digital audio engineers now face: the quality of state-of-the-art digital musical instruments will be determined not by the sophistication of the electronics within the instruments, but by how much the instruments' electromechanical components (loudspeakers, keyboards, control, switches and so forth) can be improved. The traditional skills of building vibrating structures, smooth-acting keyboards and all the other things associated with fine musical instruments are by no means dormant. They have been given new life and vitality through digital electronics. R.A.M. |

Return to Table of Contents | Previous Article | Next Article