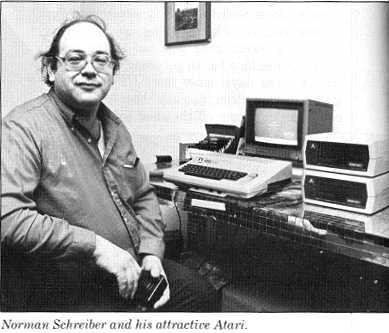

by Norman Schreiber

Norman Schreiber writes about science, traditional music and bourbon. He is a contributing editor for Popular Photography and regularly contributes to Travel & Leisure.

When you first start having an intense relationship with a computer, you feel as if you're master of the universe. Playing a game like Star Raiders on my Atari 800 certainly underscored that sense. How many hours did I spend blasting, zapping, hyperwarping and probably hyperventilating? The machine's playfulness delighted and attracted me.

Sometimes, when conducting some sort of business on the phone, I found myself absently doodling the word "Atari." I was hooked and I loved it. I loved my Atari. And why not? It was responsive. It was easy to use. I didn't have to poke around putting boards in and taking chips out. When I expanded the Atari's memory to 48K, I just snapped in a 16K RAM cartridge as if it were an 8-track tape. No muss. No fuss. No bother.

The colors it generated were great, and it offered so much ease and flexibility in generating graphics. Then Atari's word processing program came. Our relationship changed.

Writing with the Atari was fun. The Atari word processing program is menu-driven. As its questions appeared on the screen, I could swear I heard a mellifluous voice in the room. And indeed I did. The voice happened to be mine. I was reading aloud.

"Would you like to print, edit, perform other functions?"

"Do you really want to erase that file?" "How would you like your eggs?"

No, it didn't ask that last question; but I looked forward to the day when it would.

If only I hadn't listened to what the other writer guys told me. I knew all along that the Atari 800 was not looked upon as the most desirable of computers. People with conventional criteria couldn't appreciate its beautiful soul and its giving ways. They made nasty remarks about it. They smirked.

"Isn't it annoying when you're only able to look at forty columns instead of eighty?" my friend Mike asked me one day. "Don't you mind that it takes forever to format?"

"Well, you have to put a board in to get upper-and lower-case characters," I responded hotly. "I don't have to."

"But what about CP/M?" someone else asked. "Does yours have CP/M? Mine has CP/M."

I forget my retort to that one, but it makes no difference: I succumbed. I was weak and I gave in. I still loved my Atari, but I didn't respect it anymore. I just used it. Even when I was keystroking, I thought about other computers that captured my eye. Coming back from a computer exposition, I would walk quickly past the Atari. I didn't want to answer any questions. Of course, when I felt a raging need to play a game, my path was direct. There was no subtlety to my approach, and of course the Atari took all I gave.

The Atari 800 is in my son's room now. In a sense the machine has been given a promotion. Jason is sixteen and knows more about computers than I probably ever will. Sometimes he'll actually leave the sanctity of his room to show me something he's created-a new design, a new game, a program expressly designed to play with Frank Zappa music in the background. Sometimes I try to beg off. I think it's because I don't want to see how beautiful, versatile and entrancing the Atari 800 continues to be.

Return to Table of Contents | Previous Article | Next Article