PRANKSTERS OF

MICROCOMPUTING

by Allan Lundell

and Geneen Marie Haugen

Allan Lundell is the co-author of The Newest Art, on computer graphics and animation. Geneen Marie Haugen is a free-lance writer and novelist.

The year was 1971. Two silent figures were observing the entrances to SLAC, the complex that housed the Stanford Linear Accelerator. With one of the newest, shiniest atom smashers in the world, the SLAC facility at Stanford University was a physicist's dream-a center for investigation into the most basic elements of reality.

But the two observers were not interested in the nature of reality. Racing to a side entrance, they snuck past the SLAC security patrols and entered the classified high-technology library. They knew their way around, having visited the SLAC facility several times before. It was always exciting to break in; there was no limit to the information they could absorb.

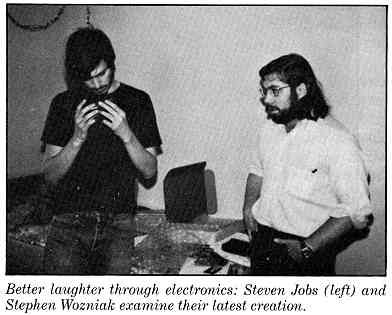

This time, however, they were on a specific mission. Thumbing through a document on multifrequency telecommunications systems, Steve Wozniak whispered to his friend Steve Jobs.

"This is it! This matches the frequencies in Esquire. With this information, we can build one!"

The future creators of the Apple II computer pulled out their pens and notebooks, scribbling data almost faster than a high-speed line printer. This was no minor treasure. They had unearthed some of the secrets of the little blue box, topic of an infamous Esquire article on phone phreaks by Ron Rosenbaum-and the magical device needed to enter the phone system, the world's electronic nervous system.

Days of intensive effort followed, until finally they held their first model, with wires and coils spilling out, up to the phone and punched out the secret touch-tone codes. After many tries and exasperating failures, the phone finally rang a long-distance number. Someone answered ...

Jobs yelled out to the person on the line: "Hello! We've got a blue box, and we are calling you from California! Where are you located?"

A little confused, their first planetary contact yelled back: "I'm in Los Angeles!"

The boys needed help. Now that they knew the Esquire story was truth and not fiction, they were sure its hero, Cap'n Crunch, must be real, too. The two Steves put out the word through the underground that they wanted to meet him.

| THE PHONE PHREAKS Phone phreaking consists of accessing the telephone network in ways that were not intended by its designers. In the late 1950s Bell Labs created the Multi-Frequency Signaling System, whose MF tones were intended to directly control the "long lines" switching network. The Touch Tone telephone dial would put out a set of tones that were completely different from the MF signaling tones. You would send Touch Tone signals to your local switching office, which would then send MF tones on up the line to instruct the network as to what telephone number you wanted to be connected to. When the MF signaling system was devised, it cost a lot of money to build the tone generators and decoders turned out by Western Electric, Bell's supplier. No one foresaw that solid-state devices would drop in price so drastically that electronic hobbyists would be able to pick up the parts at Radio Shack and just throw together something that would sound to the receiving equipment like the Bell System's equipment.   The phone phreaks discovered the MF frequencies in the Bell System Technical Journal, put out by Bell Labs for its network engineers. Published with a blue cover, the journal is called the Blue Book in the industry. It is no wonder, then, that the phreaks called their electronic wonder toy "the blue box." To show how a blue box worked, let's discuss how the network worked in general. When you place a long-distance call from your home, the number is captured by an "incoming register." (The first few digits long distance.) It then sends MF tones for the digits up the wire, and the "long lines" equipment handles it from there. When the party at the other end picks up the phone, a "supervision" signal is sent back to your central office, which means: "They picked up, so start billing." When you hang up, your central office stops the billing machine and signals are sent to "dissolve" the connection. The "long lines" machine now has to tell the machine at the other end that the call is finished by sending a tone of 2,600 Hertz down the line as an indication that the line is free. A phone phreak would dial a long-distance call, usually to an 800 "toll-free" number (800 numbers start billing at the other end of the call, that is, when the receiving party picks up the call, and billing computers at the calling party's end are instructed to disregard 800 calls on billing tapes). While the 800 number was ringing, and before anyone could pick up at the other end, the phreak would transmit a tone of 2,600 Hz into the phone line, using the blue box speaker held over the mouthpiece. The machine at the other end of the circuit "heard" that the calling party had hung up and disconnected its end of the call. When the phreak now stopped sending the tone, the machine figured, "Oh, this trunk circuit has now been seized by the other end, so I will now set up to receive signals (MF tones) telling me where to route the next call." The phreak next entered in the sequence of tones that would route his call anywhere in the world, and the phone company computer system snapped to an electronic "Yes, sir!" and connected the call. When the called party picked up the phone, the "supervision" signal was returned to the originating central office; but since that billing machine knew only that an 800 call had been placed, it threw away the billing information. It's as simple(?) as that. Let's face it, the phone phreaks had to know as much about the network as any telephone traffic engineer. They were the electronic crossword puzzle solvers of the pre-computer era. Now their brand of intellectual curiosity and ingenuity is being focused on the most complex and involving of all mind toys: the personal computer. CHESHIRE CATALYST (Richard Cheshire), telecomputer consultant and publisher of TAP, "The Hobbyist Journal for the Communications Revolution" (Room 603, 147 W 42 St., New York City 10036) |

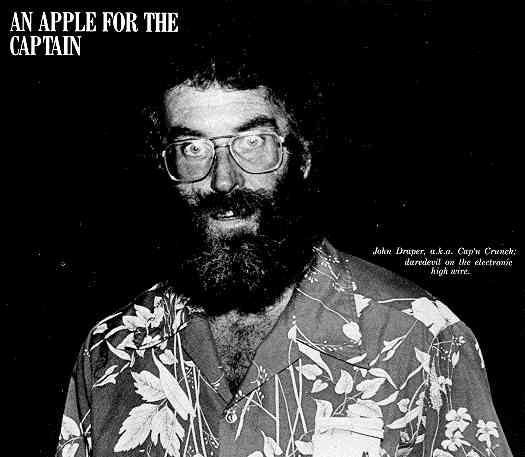

It was some meeting. The infamous Cap'n had named himself after Cap'n Crunch breakfast cereal when he'd discovered that its free bos'n whistle produced a fundamental tone for long-distance calls. He'd also gleaned phone intelligence information from Bell System publications and by making himself a nuisance at the Bell switching offices. Cap'n Crunch was charting the unknown seas of the phone system with the true Star Trek spirit of seeing what was there, going where no man had gone before and having fun doing it.

Woz had imagined Crunch to be a superengineer, a consultant to the computer industry, an ultra genius driving a van equipped to do everything but fly-a hybrid version of James Bond, the Man from U.N.C.L.E. and the professor on Gilligan's Island. But at this first meeting at the Berkeley dorms of Woz did a double take. Standing before him was, well, a madman. With long, frizzy hair, the Crunch was wild-eyed and almost toothless, like a pirate from the seven seas. All he needed was an eye patch and a wooden leg.

Cap'n Crunch launched immediately into his discoveries. After a few hours had passed, Wozniak and Jobs knew how to access different countries, overseas information operators, satellites and transoceanic cables. It was a worthwhile evening indeed.

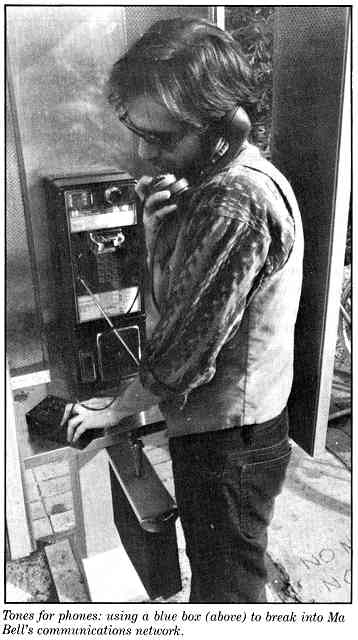

The Blue Meanies

Woz and Jobs were handed an opportunity to test out their new-found knowledge late that night. On their way to Jobs' house in Silicon Valley, the car died out near a phone booth in the low-life town of Hayward. They tried to beep their way back to Berkeley with their trusty blue box, but Woz had trouble making the connection. He was getting very nervous trying to "explain" to the operator what he was doing, when a police car pulled up and slammed on the brakes, lights flashing. The officer sauntered over to the phone booth, and the two Steves knew they'd been tricked by the operator. The officer, trained in the ways of criminals caught in the act, shifted his attention to some nearby bushes-thinking the boys had thrown something in them. In this instant, Jobs passed the blue box to Woz, who quickly shoved it in his coat pocket.

Brave move. But to no avail: the officer routinely searched both Steves and liberated them of their new tool. The officer randomly pushed buttons, and the blue box responded: bleep bleeep blup bloop!

"What's this?" he demanded.

Woz took a chance, stammering, "I-its a m-m-music synthesizer, officer."

Another police officer arrived and started trying to figure the thing out. He grilled them: "What's the orange button?"

"That's for calibration," Jobs said. "It's designed to interface with a computer."

The two boys were escorted into the back of the patrol cruiser. Feeling doomed, they were beginning to realize that being a pioneer and a prankster had its risks. Then the cop with the box turned around from the front seat and handed it to them, saying, "A good idea, but a guy named Moog beat you to it . . ."

Phone Fun

There is probably no one in the computer industry who has not heard of Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs. There are a lot of people in the industry who have heard of John Draper, alias Cap'n Crunch, and there are a lot of people who haven't. But probably everyone in Western society knows someone like them: The guy with the ham radio next door. The kid down the street who crashed his school's computer from home. The hacker in the office across the hall who's always tampering with everyone else's files. They all seem to be propelled by some inborn drive to do what few-if any-can do or have done.

These are the brethren of the high-tech frontier, the would-be merry pranksters of computerdom. The brethren break new ground, thinking the unthinkable, charting the unknown. Wherever their minds go, we will all go-eventually. No one holds the future so much in their hands as the pioneers of today's supertechnology. Thank God, they've got a sense of humor.

In the formative years of the brethren, before they'd settled on a field of specialization, when they were young and unconsciously adventurous, they were unaware of the strength of the cultural rules. For some of them, a prankstering spirit could mean disaster, but Woz and Jobs seemed to live an almost magical existence beyond the law and trouble. After mastering the blue box, they organized blue-box parties at the Berkeley dorms. Once a week, with an audience of twenty or thirty people, they held demonstrations. They'd call operators in other countries and go around the world by switching from one operator in one country to an operator in another. Finally a phone would ring in the dorm room next door. Someone would pick it up and hear Woz's voice, coming from around the world.

They'd call Dial-A-Joke in New York (Woz subsequently started his own dial-a-joke service), weather numbers in Australia, phone booths in Capetown, bars in Ireland, all amplified so the entire audience could hear. Before the night was through, everyone in the room would talk to some friend or relative in another country-all for free, all for fun. Woz was always thinking up fantastic feats for the Berkeley Blue Box Show. Everyone loved him, and he loved being the star. Before long he was calling himself Berkeley Blue and had an almost professional routine. When he was finished blowing away the audience, Blue's partner Jobs, code-named "Oct Tobor," would step in and offer shiny new blue boxes for sale-guaranteed at a low, low price of $80. Shades of things to come ...

Woz and Jobs didn't just hand-wire their boxes. Woz created them with state-of-the art technology and laid them out on personally designed printed circuit boards. This was a professional operation, a miniature high-technology company, complete with product, sales, service and support. Woz immersed himself in the tech, Jobs collected the money. Those boys sold over two hundred boxes and lived off the revenues for an entire school year.

Azure Hazards

A charmed life, some might say. But then the blue-box luck ran out. One night Woz and Jobs stopped at a pizza parlor practically next door to Woz's elementary school in the Silicon Valley town of Sunnyvale. They were on their way to Berkeley to sell a blue box, but they needed some money right away and thought they might save themselves the trip by selling it in Sunnyvale. Almost everyone feels safe in a familiar haunt in their hometown, and Jobs and Woz were no exception. Chewing their pizza, they surveyed the customers at the other tables. The families were out of the question. So were the tables full of teenagers.

But there were some really disreputable-looking characters at another table who looked as if they might be able to put the blue box to good use. Feeling confident, Wozniak and Jobs approached the table and had a low conversation about the merits of the box. Were they interested? They were interested, all right. And they were hooked after they watched a demonstration. They didn't have the money right then, so they took Woz and Jobs out to their car under the pretext of giving them their business card.

The only problem was that the business card was a gun. That blue box changed ownership pretty fast, and the shady characters drove off. They had the box-but they didn't know how to use it, and Woz and Jobs never told them. The secrets of Cap'n Crunch were safe.

In 1974 Cap'n Crunch, a.k.a. John Draper, was busted for blue-boxing. For the second time. By federal, state and local authorities. Fraud by wire was the charge. He had already spent six months in a federal penitentiary in Pennsylvania. The second time, he was sent to Lompoc-a federal pen in California.

The likable yet unfortunate Cap'n. How could he have known when he learned how to make free long-distance calls from blind kids who whistled their frequencies into the phone that he'd do time? How could he have known that the innocent free whistle inside the boxes of Cap'n Crunch cereal would lead to this? How could he have known when he blue-boxed his way to Nixon's bedside to inform the President of the nation's toilet paper crisis that he might end up in the slammer?

In Lompoc an informer for the Mafia broke his back when he refused to impart the secrets of the blue box. That was the end of Cap'n Crunch, but not of John Draper-a man described by Wozniak as being wanted by the FBI because he was "too intelligent."

If Draper hadn't been made such a folk hero by the press, it may not have gone so bad for him. Then again, his final stay in jail led him to computer fame and fortune. It was while he was in a work program that he wrote Easy Writer, the first professional-style word processing program for the Apple.

A couple of years later, IBM was looking around for software to bundle with its PC. By that time, there were better packages than Easy Writer, but someone at IBM had a sense of humor. IBM asked Draper and his new software company, "Cap'n Software," to design and program this now classic word processing package for its first entry into the personal computer market-an irony not lost on those familiar with his bouts with AT&T.

After their brushes with the dark side of the force, John Draper, Stephen Wozniak and Steve Jobs got a whole lot smarter. They wised up to some of the mysterious workings of the power structures. They lost their innocence, but they gained something else. Wozniak and Jobs struck it rich early in the Silicon Rush. They made history with their Volkswagen-like Apple Il. John Draper became wealthy enough to drive a Mercedes-Benz through the streets of Berkeley with his first release of Easy Writer for the Apple II.

New fortunes are still being made regularly in Silicon Valley, if not as often as they once were. And empires that once were, already are no longer. A new crop of microcomputer genius-pranksters are making headlines. Their exploits have inspired movies and a television show. As technology's first wave of pranksters comes of age, they are shifting their curiosity to things that are, as Wozniak explains, "creative and useful." But they're still doing things that few-if any-have done. Wozniak sponsored live satellite linkups with the Soviet Union at his outdoor musical US Festivals. Draper is masterminding a vast artificial intelligence network. Some of the other early pioneers are funding private space programs. Some are pursuing medical applications such as life-extension. Others are entering the arena of politics.

In the realm of genius-pranksters and supertechnology, just about anything is still possible. Putting the most powerful tools into the hands of individuals with creativity, integrity and courage is bound to have awesome consequences. When the real whiz kids get together to conspire, they create not simply pranks, but miracles ...

The best prank I've seen with the Apple was played by Cap'n Crunch. John Draper, one of Apple's first employees, was responsible for designing a telephone board for us. Much more than a modem, the board could send touch-tone or pulse dial data; it could also transmit any tones that were programmable down the line, listen for specific sounds and a bunch of other things. At one point Draper was motivated to crack the WATS extenders that are used by companies with incoming and outgoing free 800 lines. Company executives call in on the incoming 800 line and tap out a fourdigit code, which gets them on their outgoing 800 line. Then they can dial a free call anywhere they want. The only system protection is the four-digit code. It would take a long time to dial ten thousand phone calls manually, searching for the extender code. But Draper had designed this new telephone board, and he knew a bunch of companies that had WATS extenders. He programmed the Apple to call the company on its 800 number, automatically get to the WATS extender, type out a four-digit code and check to see if the attempt succeeded or failed. The Apple with the board would listen to all the tones on the phone line to determine when it was ringing, when it went to the WATS extender, and so on. It took about ten seconds for the Apple to dial the call and try a new four-digit code. The Apple would restart and try it again. And then try the next number. It was able to dial about five thousand calls a night-the average number of calls to crack a WATS extender. Draper cracked about twenty WATS extenders, averaging one a night. The city of Mountain View, California, where he lived at the time, keeps an index of how well the phone system is working. An average of 30 percent of all calls made from the city don't go through. The month Draper was cracking the WATS extenders, the index jumped to 80 percent! For that month Draper made more than 50 percent of the calls originating from Mountain View, California, whose population is over sixty thousand ... STEPHEN WOZNIAK |

Return to Table of Contents | Previous Article | Next Article