COMPUTER

by Carla Marie Rupp

Carla Marie Rupp is a former editor of Editor and Publisher magazine.

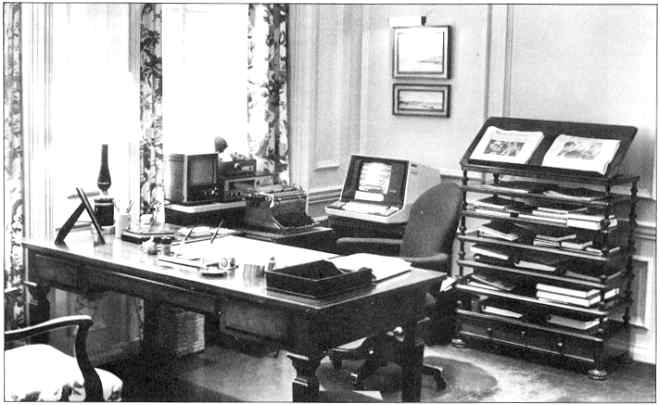

Publisher Punch Sulzberger's office illustrates the contrast in journalistic eras at the New York Times. He has two pieces of writing equipment: one a computer that links him directly with the editorial department so he can give his input, the other a 1923 Underwood typewriter. One cites the present; the other is a monument to its past.

On July 3, 1978, the New York Times caught up with the times, fully converting to computerized word processing in its editorial and news offices. By then there were over ten thousand computer display terminals in newspaper offices around the nation; but when the "newspaper of record" took the plunge, that was news. Seldom reporting on itself, the Times in its own pages amply described how it was and how it would be.

The reporter sits down at a computer terminal that hums rather than clatters. In place of a manuscript, green letters glow on a black video screen.... In principle, these 250 or so gadgets (each of which cost The Times about $9,000) more closely resemble the television games with which people play video Ping Pong than they do typewriters. But instead of manipulating electronic balls and paddles, reporters and editors compose, transpose and change the articles that appear on their screens. When the article is finished, the similarity to games ends. With the pressing of keys on the terminal, the article on its screen is moved into the computer memory of The Times.

Modern Times

As part of the early training devised by technology editor Howard

Angione terminals were placed near reporters' desks, yet the reporters

themselves were admonished to refrain from full use of the terminals

until training was complete. Such prohibition set the stage for

"forbidden fruit" benefits, with many reporters experimenting on their

own and later encouraging less adventuresome colleagues to take the

plunge.

Most people at the Times have come to swear by their

terminals. According to managing editor Seymour Topping, this is true

not only of the younger staffers, but also of the veterans on a news

department work force that numbers about one thousand.

The use of word processing here is highlighted by

the experience of Nan Robertson, who received a 1982 Pulitzer Prize for

her feature article "Toxic Shock," the most widely syndicated piece in

the history of the Times. Herself a victim of toxic shock syndrome,

Robertson wrote her article on the relatively soft-touch keys of the

video terminal after the end joints of her fingers were amputated as a

result of the disease. "The computer made it infinitely easier,"

Robertson says. "And now I'm absolutely addicted. The computer has

liberated us. Without question."

On the other hand, the Times' resident high-tech

reporter, Andrew Pollack, is acutely aware of the computer system's

limitations-including the occasional disaster known as "crashing," when

it becomes totally inoperative. One night the business section

computers crashed right at deadline and remained off for some twenty

minutes, so that all anyone could do was wait.

A vocal defender of the First Amendment, the Times

has had to confront important questions about privacy and freedom on

its own computers. Each staffer can store information on a personal

directory accessed by a simple password, usually the computer user's

initials. Though such files should be used only for information

pertaining to putting out the paper, reporters and editors have gotten

into the habit of storing video games like "Nessie," a cartoon of the

Loch Ness monster with a toothy grin. Times management in the person of

James Greenfield issued an internal memo, saying in part: "Games and

visual oddities may not be played or stored in the computer. They

clutter the storage disk and slow its operation; they also encourage

browsing, which leads to privacy violations." One serious violation of

a reporter's privacy recently resulted from malicious colleagues

printing out a love letter in her personal directory and passing it

around the newsroom. The Times has announced a policy of running spot

checks on files and deleting any unauthorized copy, raising an issue

the Newspaper Guild intends to confront in forthcoming contract

negotiations.

Health Cares

There has also been concern among employees about health hazards

associated with word processors. When VDTs were first introduced at the

paper, several veteran typesetters came down with cataracts. The safety

of VDTs became an issue in union contract arbitration talks with the

Times. The U.S. government's National Institute for Occupational Safety

and Health (NIOSH) was called in to investigate but found no excessive

levels of radiation nor a sufficient number of cases to prove or

disprove any correlation between cataracts and computers. Arbitration

in 1975-76 went against the Newspaper Guild for not showing sufficient

evidence linking terminals and cataracts.

Copy editor David Unger, who works on safety and

health issues for the Newspaper Guild Times unit, says people at the

paper "remain skeptical. I tell them I can't give them a guarantee that

it's safe, and I have to press to get radiation standards lower and

lower." The union's focus continues on the need for rest breaks, proper

furniture and glare-free lighting. Unger says the Times has made

progress in providing proper chairs, and the Guild has planned

discussions regarding the glare in the newsroom.

In answer, Dr. Howard Brown, medical director for

the Times Company, comments: "The fact is that long and intensive study

in many places and over many years by many governmental and

professional organizations have cleared VDT terminals of medical `scare

myths.' NIOSH, for example, and the Food and Drug Administration, as

well as the Canadian Department of National Health and Welfare,

Radiation Protection Bureau, have each cleared VDT terminals of causing

cataracts or birth defects."

New Papers

Today the redecorated, carpeted, modern newsroom is as quiet as an

airport waiting area at 4 A.M. You don't hear the old-fashioned clatter

of the deadline approaching. You just see people concentrating at their

machines. Looking toward the future, the Times' extensive computerized

editorial operations may soon be outdated by further computerized

advances in the newspaper industry. Today's system and tomorrow's

equipment may offer as much of a contrast as Sulzberger's typewriter

and computer.

Return to Table of Contents | Previous Article | Next Article