SOFTWARE STAR

TRADING CARDS

CLIVE SINCLAIR

In 1972, as a rookie, England's Clive Sinclair created land marketed a handheld calculator. That failed because his calculations ignored the lower-priced competition from Oriental manufacturers, A few seasons later, he entered the digital watch business with Black Watch, an unfortunately accurate name, components were difficult to get and time ran out.

Switching his stance, Sinclair belted out the Sinclair ZX-80 and ZX-81, small 2K computers originally retailing for $159.95 at a time when popular microcornputers cost upward of $1,000 The new Sinclair players captured the imagination of non-computernik fans, who embraced them as a relatively cheap introduction to computing. Through a marketing deal with Timex in the United States, the Sinclair ZX-80 became known as the Timex 1000 and went on to set popularity records during its meteoric rise and fall. In England, Sinclair kept his streak gang with the Spectrum and QL computers, but was held hitless in the United States by strong marketing competition.

SEYMOUR RUBENSTEIN

During a career of over a dozen years in the majors, Seymour Rubenstein served as a utility player with Sanders Associates in New Hampshire and with IMSAI in California. He then started his own software organization and led it to a perennial World Series on the strength of its ace word processor. WordStar.

Rubmstein created the software's specifications and commissioned programmer Rob Barnaby to follow through. Since its introduction in 1979 WordStar has been enjoyed by over a million fans, though not all have been paying customers.

Benched by a heart attack in 1983, Rubenstein made a valiant comeback bid thal coincided wdh his company scoring impressively through its first public offering of stock. Lately he has been seen in the bullpen coaching Rob Barnaby on the next entry in ft MicroPro line-up, a hush-hush program that just may be the successor to WordStar.

FERNANDO HERRERA

In 1982 Fernando Herrera earned rookie-of-the-year honors with My First Alphabet, the original recipient of Atari's annual $25,000 Star of Merit award. Herrera created the program to help his son, who had been born with cataracts, Told by doctors that he would have to wait a few years before knowing if the boy would be able to see. Herrera used his new Atari to create bright, colorful letters and pictures on his TV screen It worked. His son could see them.

The save-the-earth arcade-style game Astrochase, released by Herreras First Star software firm in 1993, landed him another winner with graphics worthy of the Hall of Fame. Looking for a fireballing reliever to acquire, the electronic publishing arm of Warner Communications ended up buying a piece of his organization, and since then Herreras teammates have scored another first, licensing games written in personal computers for play in video arcades. First Star indeed.

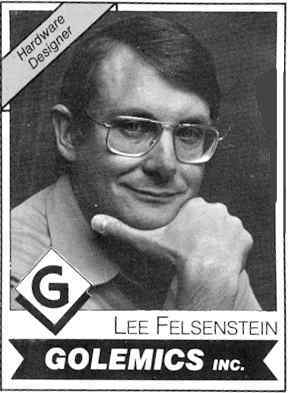

LEE FELSENSTEIN

Lee Felsenstein broke into the personal computer majors in 1975 when he helped found a dynasty of computer sluggers at the Homebrew Computer Club, the original personal computer user group.

During the 1976 season he fielded the first successful self-contained personal computer, the Sol20, for Processor Technology. Though the machine has since gone the way of Satchel Page, the Sol-20 is always a crowd-pleaser on Old-Timers' Day.

As vice-president of engineering at the Osbome Computer Corporation, Felsenstein changed the rules of the game by designing the Osbome-1, the first portable computer. The team's front office then blew its imposing lead, landing in the bankruptcy courts.

Felsenstein's own team, Golemics Inc., permits him to play different positions, designing hardware for various manufacturers and furthering the establishment of Community Memory a protect to bring computer terminals to public places like shopping mall, and even ball parks.

BILL BUDGE

In college Bill Budge pulled off a rare double play by earning two bachelor degrees (in science and math) at the same time. After four years of working toward a PhD, he acquired an Apple, lost interest in the doctorate and decided to turn pro.

Budge learned to play pinball while he was studying micro programming. His training ground was the now defunct Galaxy Family Skills Center in Cupertino, California, once frequented by pioneer players including Stephen Wozniak (See Hardware and Software Stars #1). In 1981 his own company leased Raster Blaster, the classiest of computer pinball simulation games. His reproduction of a ball caroming off bumpers and flippers was nothing less than an inside-the-park home run.

Then came a grand-slammer with Bill Budge's Pinball Construction Set, published by Electronic Arts. Here the players can construct their own pinball games from scratch using icon-like elements provided by Budge.

GARY KILDALL

Gary Kildall's personal computer career began when he batted around the idea for a coin-operated astrology computer for arcades but found he lacked the operating system software to make it a reality. Writing such software and improving it after the astrology machine turned out impractical, the resulting CP/M (Control Program for Microprocessors), marketed by his Digital Research firm, became a league leader as the first standard for desktop business computer applications.

Kildall's winning streak snapped when IBM went searching elsewhere for an operating system for its PC. The proliferation of IBM clones relegated CP/M to the second division. But Kildall came out of left field by designing DR Logo, his own version of the popular Logo language, for the IBM PC. He later improved its home run potential by adding commands that would make it useful in controlling video disk players.

| COMPUTER BALL It's surprising that baseball has taken so long to get around to using computer technology. After all, computers have become a fixture in our everyday lives and baseball is our national pastime. In the late 1960s one old gent did take pains to record the deeds of the Chicago Cubs on IBM punch cards and run them through a computer at the Wrigley factory, but the stats were in no useful form and the method failed to catch on. The game of inches had to wait for more sophisticated and comprehensive software for microcomputer systems. Today, computers are safe at home in the offices and dugouts of the Chicago White Sox and Oakland A's, who pioneered in their use, and of the Toronto Blue Jays, New York Yankees and Mets. The most popular statistics program is The Edge 1.000, which can do everything but spit tobacco juice. The Edge was developed by Dick Cramer, Philadelphia pharmaceutical designer by day, nighttime baseball fanatic and self-proclaimed "sabremetrician" of the Society for American Baseball Research. Sabremetricians are revisionist statisticians (though they dislike the term) who scientifically apply the minutiae they glean in wholly new ways. They claim, for example, that it never pays to bunt; a runner should almost always try to go from first to third on a single because it's a high-percentage play. Their ideas regarding baseball are considered unorthodox and even outrageous by most big-league managers, who swear the bunt will always remain in their offensive arsenals. Cramer wrote The Edge during the infamous baseball players' strike in the middle of the 1981 season. When big-league play resumed, his lone client was the Oakland A's, who originally wanted the stats for the broadcast booth. With team statistician Jay Alves carefully entering every pitch and every hit, walk, out, wild pitch, passed ball, sacrifice and stolen base (known electronically as "events"), the results could be displayed on a remote monitor in the broadcast booth. Announcer Bill King recalls that one day he casually told his listeners that Al Bumbry was sixfor-fourteen lifetime against Tom Underwood and "damned if Bumbry didn't get three hits off him in that ball game." It wasn't long before someone suggested giving such useful data to the As then manager, Billy Martin-who, being of the old school, threw the printouts away. When Steve Boros replaced Martin as the A's skipper, the first thing he wanted to know was where Oakland kept its computer. Boros was a nouvelle baseball man. Whenever he was on the road, his hotel suite would be littered with file folders of the team's latest stats. The computer figured in 5 percent of his managerial decisions, although many of his players were dead-set against it. Rickey Henderson, the dean of base stealers, was skeptical. Center fielder Dwayne Murphy openly despised the machine. Carney Lansford politely ignored it.  New York Mets manager Dave Johnson started the 1984 season bullish on computers. This holder of a master's degree in math couldn't find the algorithm for keeping his team from slumping in midseason. The players' objections were sometimes moot. When the A's were in a long slump, manager Boros asked the computer for a "pitching count" breakdown. Were his hitters swinging at too many pitches? Shortstop Bill Almon was a guinea pig. According to the computer, when the count was three balls, no strikes or three and one, Almon was hitting .600 or better. When the count was two and two or three and two, he was hitting around .100. Didn't Almon already know that he hit well when he was ahead in the count and poorly when he got behind the pitcher? Yes, the computer merely confirmed what everyone knew. So far the most dramatic use of computers in the sport of baseball has been off the field or in altering the field itself. Recently the White Sox management, who use the machine mostly in the front office, boasted an 11-2 win-loss record in salary arbitration with its players. You can bet that when pitcher Dennis Lamp asked for a half-million-dollar raise, the computer printouts were whipped out by the Sox' negotiators. (Lamp lost in arbitration.) And after looking over a computer analysis of all inside-the-park fly balls caught over 350 feet in Comiskey Park, the Sox front office realized that 84 were hit by the Sox and only 50 by opponents. To give the local team an added advantage in scoring with the long ball, home plate was moved eight feet closer to the fences at the start of the 1983 season. While computers have yet to work miracles in major league baseball, it is simply a matter of time before one team's success will cause every other club to get a computer. As soon as a high-tech team wins a World Series, every front office will want one- much like the rush caused by the Dallas Cowboys in pro football, where almost every team now has one. DOUG GARR, editor of Video magazine and author of "Woz," a biography of Stephen Wozniak. |

Return to Table of Contents | Previous Article | Next Article